I was educated at Stowe, and at Pomfret School in New England, where I went for a year on an English Speaking Union Scholarship. There were quite a few boys at Stowe during my time there who later became professional actors or directors – Toby Robertson and Edward Hardwicke were two of my contemporaries – and I still remember my first review as the Duke of York in ‘Richard the Second’ from Beverly Baxter, the theatre critic of the ‘Evening Standard’: ‘J. Burnham moved and spoke well, despite a hat that was inclined to get in the way of his face’.

I was educated at Stowe, and at Pomfret School in New England, where I went for a year on an English Speaking Union Scholarship. There were quite a few boys at Stowe during my time there who later became professional actors or directors – Toby Robertson and Edward Hardwicke were two of my contemporaries – and I still remember my first review as the Duke of York in ‘Richard the Second’ from Beverly Baxter, the theatre critic of the ‘Evening Standard’: ‘J. Burnham moved and spoke well, despite a hat that was inclined to get in the way of his face’.  At Pomfret, my performance as Koko in ‘The Mikado was described by the local newspaper as ‘ingratiating’. I took this to mean that I had played the part like Uriah Heap, but was assured that the word had a more favourable meaning on the other side of the pond.

At Pomfret, my performance as Koko in ‘The Mikado was described by the local newspaper as ‘ingratiating’. I took this to mean that I had played the part like Uriah Heap, but was assured that the word had a more favourable meaning on the other side of the pond.  At the end of my year in America, three of my schoolmates and I were driving across the States to California when we were arrested for murder just outside Springfield Missouri, where all the cops look like Rod Steiger. It happened thusly. Unknown to us, someone had been murdered the previous night in the wood where we were camping. We suddenly found ourselves surrounded by a ring of gun-toting Rod Steigers who told us to come out with our hands up. They took us to Springfield jail – past a sign saying ‘30 m.p.h. – and we don’t mean maybe!’ – and we spent the night in the juvenile cells. They grudgingly let us go in the morning, advising us to ‘get out of town fast’. Safely back in London, I auditioned for the Old Vic School, run by three great men of the theatre – Michel St. Denis, Glen Byam Shaw and George Devine. Despite being told by Glen that the pieces I had chosen – from Cyrano de Bergerac and Richard the Second – were ‘not exactly your parts, dear boy’, I was accepted.

At the end of my year in America, three of my schoolmates and I were driving across the States to California when we were arrested for murder just outside Springfield Missouri, where all the cops look like Rod Steiger. It happened thusly. Unknown to us, someone had been murdered the previous night in the wood where we were camping. We suddenly found ourselves surrounded by a ring of gun-toting Rod Steigers who told us to come out with our hands up. They took us to Springfield jail – past a sign saying ‘30 m.p.h. – and we don’t mean maybe!’ – and we spent the night in the juvenile cells. They grudgingly let us go in the morning, advising us to ‘get out of town fast’. Safely back in London, I auditioned for the Old Vic School, run by three great men of the theatre – Michel St. Denis, Glen Byam Shaw and George Devine. Despite being told by Glen that the pieces I had chosen – from Cyrano de Bergerac and Richard the Second – were ‘not exactly your parts, dear boy’, I was accepted.

MY WORK AS A BRITISH ACTOR

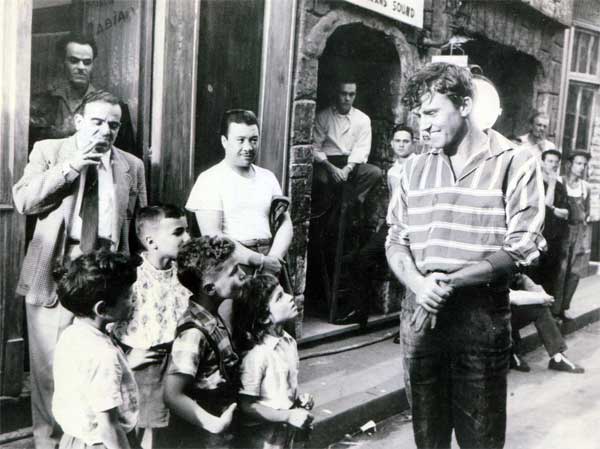

After graduating from the Old Vic School, I spent two years in rep at Salisbury and Nottingham before a good review in ‘The Stage’ of my performance in Anouilh’s ‘Point of Departure’ brought me to the notice of H.M. Tennent, at that time the most powerful management in the West End.I was invited to audition for the part of Robert Morley’s son in ‘Hippo Dancing’. The play was a big hit, and ran for fifteen months at the Lyric Theatre. This was followed by two other hits: ‘The Rehearsal’, starring Alan Badel and Maggie Smith, which occupied the Globe Theatre for nearly a year…and E.M. Forster’s ‘A Passage to India’, which ran for seven months at the Comedy Theatre. It had a huge cast, and on the opening night in Oxford Forster thanked the actors for not only being so good, but so many! Along with the hits, though, there were inevitably misses, some of which failed despite excellent notices. There was ‘No Concern of Mine’ at the Westminster Theatre, ‘Once More with Feeling’ with John Neville and Dorothy Tutin at the Albery, and ‘The Platinum Cat’ at Wyndham’s. This starred a miscast Kenneth Williams, who often enlivened sparsely attended matinees by inventing new (and sometimes extremely pornographic) dialogue. There were also two memorable Shakespearean tours – the first with the RSC in John Gielgud’s production of ‘Much Ado about Nothing’ and George Devine’s production of ‘King Lear’. Led by Gielgud and Peggy Ashcroft, the tour, which included a nine-week season at the Palace Theatre in London, was a sell-out all over Europe. The problem was that though ‘Much Ado’ was rapturously received everywhere, ‘Lear’ was a disaster. Designed by Isamu Noguchi, better known as a sculptor, the production might have worked if there had been a new acting style to go with the outlandish Japanese costumes. But there was a complete mismatch between the primitive and the traditional, which Gielgud obviously sensed at the dress parade. He was given a series of cloaks, with larger and larger holes in them to represent Lear’s growing madness. ‘I’m terribly worried about this, George’, he kept saying to George Devine. ‘I look like a gruyere cheese’. By contrast, his own production of ‘Much Ado’ was a delight. On the opening night in Vienna, the audience stood and applauded for over ten minutes, then rushed round to the stage door and applauded each actor as they came out. But after the ‘Lear’ premiere later in the week, the street was deserted. Another Shakespearean tour – this time of the Middle East under the auspices of the British Council, in which I played Toby Belch in ‘Twelfth Night’ – was memorable for the bizarre incidents that kept happening both on and off the stage. On the first night in Rawalpindi, Richard Heffer as Orsino had just begun his opening speech – ‘If music be the food of love, play on’ – when a cat wandered onto the stage, sat down near the footlights and stared at the audience as if it was wondering what they were doing there. Richard struggled bravely on through the ensuing laughter, but a few minutes later the generator broke down and all the lights went out. It took about twenty minutes to fix the problem, but nothing could be done when the generator finally gave up the ghost. The actors had to finish the play holding candles under their faces, but they received little reward for their resourcefulness. In the papers the next morning, the cat got all the notices. In Sri Lanka, the next country we visited, the first performance in Colombo was interrupted by a parade of trumpeting elephants passing by the theatre. But this was nothing compared with the deafening roar made by a matinee audience of excited schoolchildren at the next date, Galle. It was the first time the Singhalese boys and girls had been allowed to sit together, and they were far more interested in each other than in Shakespeare. The wall of noise was so all-enveloping that the actors couldn’t hear each other, even though they were only a few feet apart. At the interval, a teacher announced that anyone who wanted to leave could do so, and about half the audience took advantage of the offer. The ear-splitting racket subsided just enough for us to finish the play, and when we returned to our hotel a group of Americans who had been at the performance applauded us. ‘We think you are the bravest people we know’, one of them said. But in Baghdad, things became more serious. We arrived in the middle of the Iran-Iraq war, and missiles were landing in the city. There was a blackout at night – except for the international hotels, which were ablaze with light. It would have suited Saddam Hussein’s propaganda machine if some visiting British thespians had been blown up. The British Council had warned the company about the tricky political situation in Iraq, and warned us not to say anything in public that could be construed as criticism of the regime. The atmosphere was certainly very tense, and on the first night in Baghdad, attended by several government ministers, republican guards with machine guns were stationed not only round the theatre, but backstage. Unfortunately, no-one had told them that ‘Twelfth Night’ begins with a storm and a shipwreck. So when the first crack of thunder echoed round the theatre, the nervous guards thought it was an attack and raised their guns. I started to wonder if I should have chosen a less dangerous profession. Parallel with my theatre work, I made many appearances in films and TV plays. This is me, on location in the Rue de la Huchette in Paris, playing Jean Seberg’s boyfriend in ‘Bonjour Tristesse’.

After graduating from the Old Vic School, I spent two years in rep at Salisbury and Nottingham before a good review in ‘The Stage’ of my performance in Anouilh’s ‘Point of Departure’ brought me to the notice of H.M. Tennent, at that time the most powerful management in the West End.I was invited to audition for the part of Robert Morley’s son in ‘Hippo Dancing’. The play was a big hit, and ran for fifteen months at the Lyric Theatre. This was followed by two other hits: ‘The Rehearsal’, starring Alan Badel and Maggie Smith, which occupied the Globe Theatre for nearly a year…and E.M. Forster’s ‘A Passage to India’, which ran for seven months at the Comedy Theatre. It had a huge cast, and on the opening night in Oxford Forster thanked the actors for not only being so good, but so many! Along with the hits, though, there were inevitably misses, some of which failed despite excellent notices. There was ‘No Concern of Mine’ at the Westminster Theatre, ‘Once More with Feeling’ with John Neville and Dorothy Tutin at the Albery, and ‘The Platinum Cat’ at Wyndham’s. This starred a miscast Kenneth Williams, who often enlivened sparsely attended matinees by inventing new (and sometimes extremely pornographic) dialogue. There were also two memorable Shakespearean tours – the first with the RSC in John Gielgud’s production of ‘Much Ado about Nothing’ and George Devine’s production of ‘King Lear’. Led by Gielgud and Peggy Ashcroft, the tour, which included a nine-week season at the Palace Theatre in London, was a sell-out all over Europe. The problem was that though ‘Much Ado’ was rapturously received everywhere, ‘Lear’ was a disaster. Designed by Isamu Noguchi, better known as a sculptor, the production might have worked if there had been a new acting style to go with the outlandish Japanese costumes. But there was a complete mismatch between the primitive and the traditional, which Gielgud obviously sensed at the dress parade. He was given a series of cloaks, with larger and larger holes in them to represent Lear’s growing madness. ‘I’m terribly worried about this, George’, he kept saying to George Devine. ‘I look like a gruyere cheese’. By contrast, his own production of ‘Much Ado’ was a delight. On the opening night in Vienna, the audience stood and applauded for over ten minutes, then rushed round to the stage door and applauded each actor as they came out. But after the ‘Lear’ premiere later in the week, the street was deserted. Another Shakespearean tour – this time of the Middle East under the auspices of the British Council, in which I played Toby Belch in ‘Twelfth Night’ – was memorable for the bizarre incidents that kept happening both on and off the stage. On the first night in Rawalpindi, Richard Heffer as Orsino had just begun his opening speech – ‘If music be the food of love, play on’ – when a cat wandered onto the stage, sat down near the footlights and stared at the audience as if it was wondering what they were doing there. Richard struggled bravely on through the ensuing laughter, but a few minutes later the generator broke down and all the lights went out. It took about twenty minutes to fix the problem, but nothing could be done when the generator finally gave up the ghost. The actors had to finish the play holding candles under their faces, but they received little reward for their resourcefulness. In the papers the next morning, the cat got all the notices. In Sri Lanka, the next country we visited, the first performance in Colombo was interrupted by a parade of trumpeting elephants passing by the theatre. But this was nothing compared with the deafening roar made by a matinee audience of excited schoolchildren at the next date, Galle. It was the first time the Singhalese boys and girls had been allowed to sit together, and they were far more interested in each other than in Shakespeare. The wall of noise was so all-enveloping that the actors couldn’t hear each other, even though they were only a few feet apart. At the interval, a teacher announced that anyone who wanted to leave could do so, and about half the audience took advantage of the offer. The ear-splitting racket subsided just enough for us to finish the play, and when we returned to our hotel a group of Americans who had been at the performance applauded us. ‘We think you are the bravest people we know’, one of them said. But in Baghdad, things became more serious. We arrived in the middle of the Iran-Iraq war, and missiles were landing in the city. There was a blackout at night – except for the international hotels, which were ablaze with light. It would have suited Saddam Hussein’s propaganda machine if some visiting British thespians had been blown up. The British Council had warned the company about the tricky political situation in Iraq, and warned us not to say anything in public that could be construed as criticism of the regime. The atmosphere was certainly very tense, and on the first night in Baghdad, attended by several government ministers, republican guards with machine guns were stationed not only round the theatre, but backstage. Unfortunately, no-one had told them that ‘Twelfth Night’ begins with a storm and a shipwreck. So when the first crack of thunder echoed round the theatre, the nervous guards thought it was an attack and raised their guns. I started to wonder if I should have chosen a less dangerous profession. Parallel with my theatre work, I made many appearances in films and TV plays. This is me, on location in the Rue de la Huchette in Paris, playing Jean Seberg’s boyfriend in ‘Bonjour Tristesse’.  But it was through the popular TV series such as ‘The Saint’, ‘Danger Man’, ‘The Persuaders’ and ‘The Avengers’ that many actors earned their bread and butter. I appeared in all of them, some several times, usually playing villains.

But it was through the popular TV series such as ‘The Saint’, ‘Danger Man’, ‘The Persuaders’ and ‘The Avengers’ that many actors earned their bread and butter. I appeared in all of them, some several times, usually playing villains.  It was while filming my third ‘Avengers’, shortly after my marriage to the actress Veronica Strong (whom I met on Platform 6 in Victoria station) that a conversation with Patrick McNee led to a new career….

It was while filming my third ‘Avengers’, shortly after my marriage to the actress Veronica Strong (whom I met on Platform 6 in Victoria station) that a conversation with Patrick McNee led to a new career….

MY WORK AS A BRITISH WRITER

I had always written stuff: at school, in America, between acting jobs. By the time I told Patrick McNee that I would like to try my hand at ‘The Avengers’, I had already had one or two TV scripts accepted. At Patrick’s suggestion, I went to see Brian Clemens, the producer, who happened to be looking for writers. Brian liked the story idea I mentioned, and commissioned the script. This, too, met with his approval, which led to a two-year contract to write for the show. I contributed five episodes, and at a recent ‘Avengers’ fiftieth anniversary convention in Chichester I was surprised to find myself an object of interest, because I was the only person who both appeared in and wrote for the show. The producer’s instructions were ‘ For God’s sake, don’t let anything happen!’ I then became a full-time writer, contributing episodes for many well-known TV series. There were also original screenplays, novel adaptations, children’s series and books. (see filmography). Three of the latter – ‘Children of the Stones’, ‘Raven’ and ‘Mystery of the Tower’ were written in collaboration with Trevor Ray. ‘Children of the Stones’, filmed in 1977, became – and still is – a cult children’s serial all over the world. Even now, thirty-five years later, it is remembered and cherished by adults who watched the series from behind the sofa when they were kids. SFX magazine still rates it as one of the scariest stories in the history of television. The book and DVD are still selling well, schools still choose it as a set book, an American composer is currently turning it into an opera, and as recently as October 2012, Radio 4 did a programme about it.  My wife Veronica was touring Israel with Alan Bennett’s ‘Habeas Corpus’ shortly after ‘Children’ had ended, when she received a visit from the British ambassador after the show. He’d read in the programme that she was married to me, and as his family had had to miss the last episode, he wondered if, in exchange for lunch at his club in London, we could tell him what happened. She agreed to the deal, and a few months later we presented him with a copy of the book. I hope that fans of the show will be glad to know that I have finally finished the sequel – ‘Return to the Stones’. It has just been published (November 2012) as a kindle ebook, along with ‘Children’, ‘Raven’, ‘Mystery of the Tower’ and ‘Break Point’ (a children’s serial about a young tennis champ I wrote for the BBC). All of them are on sale at Amazon. Yes, I still write. I live in Somerset with Veronica, and recommend Platform 6 at Victoria station as an excellent place to meet future wives. I have three sons, five (soon to be six) grandchildren and a cat called Bubble who helps me with my scripts.

My wife Veronica was touring Israel with Alan Bennett’s ‘Habeas Corpus’ shortly after ‘Children’ had ended, when she received a visit from the British ambassador after the show. He’d read in the programme that she was married to me, and as his family had had to miss the last episode, he wondered if, in exchange for lunch at his club in London, we could tell him what happened. She agreed to the deal, and a few months later we presented him with a copy of the book. I hope that fans of the show will be glad to know that I have finally finished the sequel – ‘Return to the Stones’. It has just been published (November 2012) as a kindle ebook, along with ‘Children’, ‘Raven’, ‘Mystery of the Tower’ and ‘Break Point’ (a children’s serial about a young tennis champ I wrote for the BBC). All of them are on sale at Amazon. Yes, I still write. I live in Somerset with Veronica, and recommend Platform 6 at Victoria station as an excellent place to meet future wives. I have three sons, five (soon to be six) grandchildren and a cat called Bubble who helps me with my scripts.